Newspaper Cuttings and Books from Queen Mary Hospital Sidcup and Queen Mary Hospital Roehampton

Emmeline Burdett

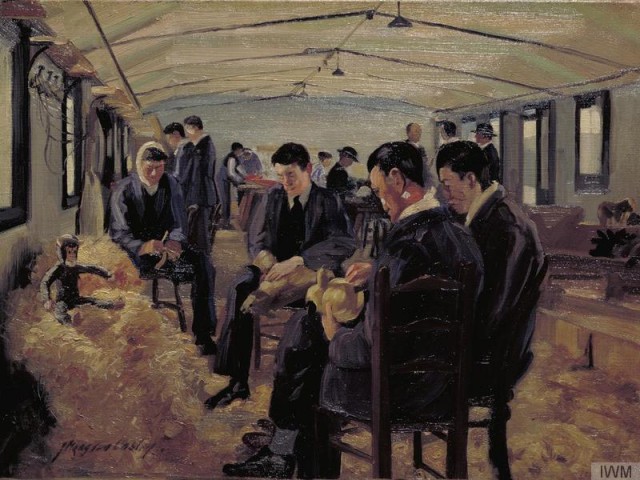

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) in Clerkenwell holds a number of fascinating newspaper cuttings books dating from c.1917-1921. These newspaper cuttings pertain to the Queen Mary Hospital Roehampton and to its sister hospital, Queen Mary Hospital Sidcup. Both of these hospitals were set up during the course of World War One in response to the enormous numbers of wounded soldiers being sent back from the Front to English hospitals, and the resulting strain on the medical system. Queen Mary Hospital Roehampton treated men whose wounded limbs required amputation, whilst Queen Mary Hospital Sidcup pioneered new techniques of facial reconstruction. So far, I have looked at two of the scrapbooks: the Founder’s Scrapbook from the Roehampton hospital (H02/QM/Y/05/002), and the newspaper cuttings’ book from the Sidcup hospital (H02/QM/Y/01/005).

I first became aware of the existence of these scrapbooks a few months ago, as I go to a monthly book group at the LMA which is run by Claire Titley, one of the archivists. When the book group meets, Claire always brings along some of the LMA’s holdings which relate to the book we are reading. In this case the book was My Dear I Wanted to Tell You, by Louisa Young. The novel is set during the First World War and the main character, Riley Purefoy, is seriously wounded at the Front. He is taken back to England, and treated at Queen Mary’s Hospital Sidcup. Claire had brought out the two scrapbooks mentioned above, and she remarked upon how strikingly different the tone was between the two. The one pertaining to Roehampton was upbeat, with photographs of amputee soldiers playing sports, showing how competent they were, and making preparations for a return to civilian life. That pertaining to the Sidcup hospital was in stark contrast, containing doom-laden descriptions of the men being treated there, and seeming to accept that, due to their facial disfigurements, these men were destined to be social outcasts for evermore. Of course, during the book group session it was only possible to have a cursory look at the scrapbooks, so I was eager to take the opportunity to return and investigate them more closely.

There did appear to be a sound practical reason for giving these men trades which required them to spend much of their time in the open air. Many of the early newspaper reports from the hospital specifically mention that the disfigured men were often subject to low spirits, and that spending time in the open air seemed to help alleviate this. [5] It is, however, striking that the men’s depression of spirits was mentioned at a time when the hospital was engaged in fundraising for equipment, but this approach came into its own when the Evening Standard newspaper began fundraising for a Recreation Fund to help keep the Sidcup patients occupied. Men who had previously been suffering from low spirits suddenly became ‘the most tragic of all war’s victims’. [6] Facial disfigurement was described as ‘the worst loss of all’ [7] The Fund finally closed in the summer of 1918, having raised nearly £10,000, a fortune in today’s money. The descriptions of the Sidcup patients had clearly tugged successfully upon society’s purse-strings.

To talk of the social model of disability in relation to the early twentieth-century would clearly be anachronistic. Nevertheless, the parallel between the increasingly heart-wrenching descriptions of the Sidcup patients and the initiatives to raise money for them do, I feel, open the door to the idea that these things are open to discussion and investigation. Disability history has sometimes been held back by an impression amongst some that to enquire into these areas would be insensitive or ghoulish.

Dr Emmeline Burdett is an independent scholar.

Guest post for Disability and Industrial Society’s UK Disability History Month Blogs 2014.

http://www.dis-ind-soc.org.uk/en/blog.htm?id=40

[1] Roehampton, p.13. Sunday Herald newspaper report from July, 1917. Entitled ‘Hearts of Oak: Roehampton Style’, it is one of the many illustrated reports contained in the Roehampton scrapbook.

[2] Roehampton, p.21. Report from the Glasgow Bulletin entitled ‘What Science Does for the Limbless Soldier’ showing a Roehampton inmate using his artificial arm to chop wood.

[3] Roehampton:p.79. Report from The Hospital, entitled ‘Dancing in Relation to the Use of Artificial Legs’ detailing how Monsieur Jean Castener, a dancer from the Adelphi Theatre, taught dancing to men with an artificial leg, at the Physico-Therapeutic Department of St. Thomas’s Hospital.

[4] Sidcup: p.1.

[5] Sidcup, p.13 and p.21. Fundraising letter in the Morning Post, the Newcastle Daily Chronicle, the Dundee Courier, the Edinburgh Despatch, the Glasgow Herald and the Monmouth Evening Post.

[6] Sidcup, p. 36.

[7] Sidcup, p.37. Article from the Manchester Evening Chronicle.