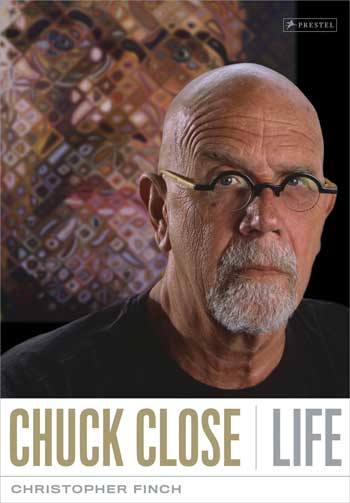

Chuck Close

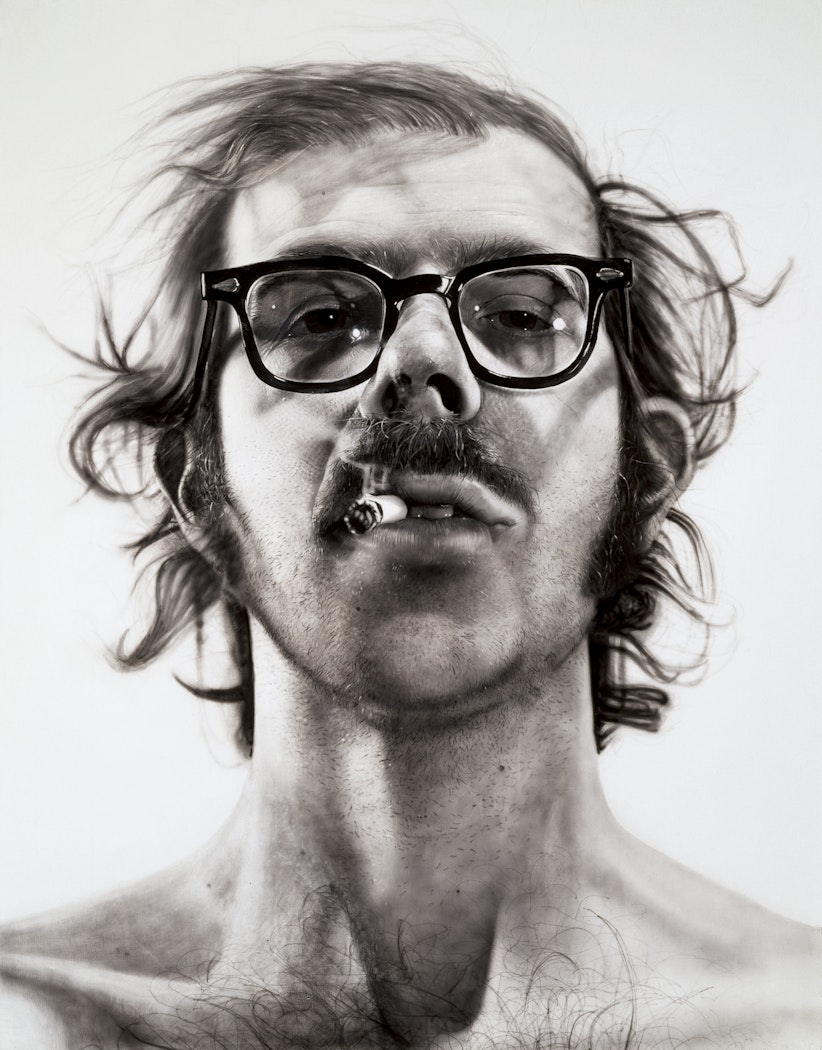

Image source: F News Magazine

The famous photorealist painter had to overcome many hardships in his life, but not without learning the value of perseverance.

Chuck Close, most famous for his large-scale portraits that are divided into grids and painted, has to move around in a wheelchair due to a collapsed spinal artery in his back. He also suffers from prosopagnosia, or face blindness, where he can’t recognize faces.

Close also lives with dyslexia, something that wasn’t recognized when he was growing up.

“(At that time) there was no such thing as dyslexia,” he tells F News Magazine. “[People thought] you were just dumb and lazy.”

Close had trouble remembering names and dates, but worked hard to show success in school. He sat in the front rows, participated frequently, and even would sit in a dark room, shining a flashlight on a page of text and read it out loud until he remembered.

But the best way Close got through school was by making art. He would “drag extra-credit murals and maps and charts into class” to prove to his teacher that he was neither dumb nor lazy.

Despite his dyslexia, Close became successful in his pursuit of art. He lived by the motto “Go to Yale or go to jail,” striving for a successful art career at the university. His parents were supportive of his love for art, which gave him the motivation to work hard.

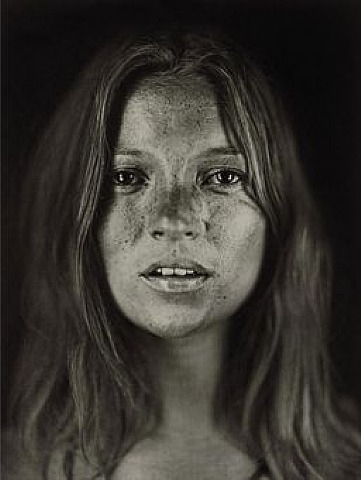

Big Self Portrait 1968

With his perseverance, he was able to earn a scholarship to Yale summer school, and eventually a scholarship to Yale University, where he met many influential artists.

During a time when abstract expressionism — the big, messy tableaus that were made famous by Jackson Pollock — was on the decline, American art needed something new. Close’s peers and mentors helped Close find a unique medium, and there he got into photorealism.

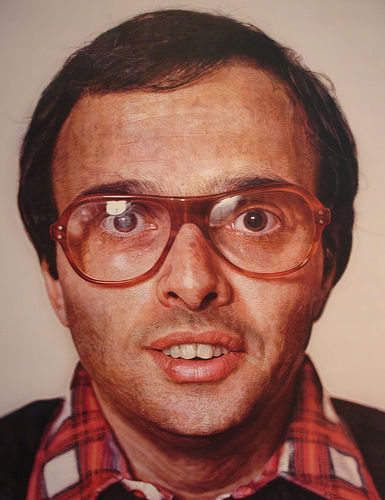

Mark 1978

Leslie 1986 Agnes 1998

Kate Moss 2005

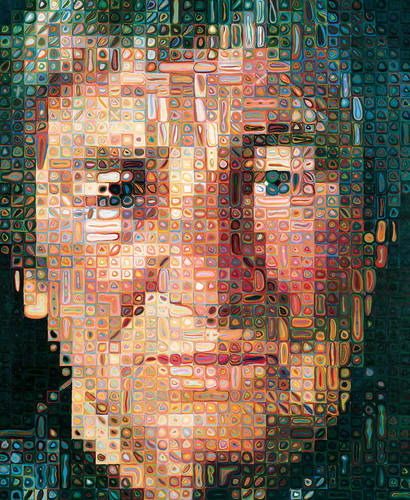

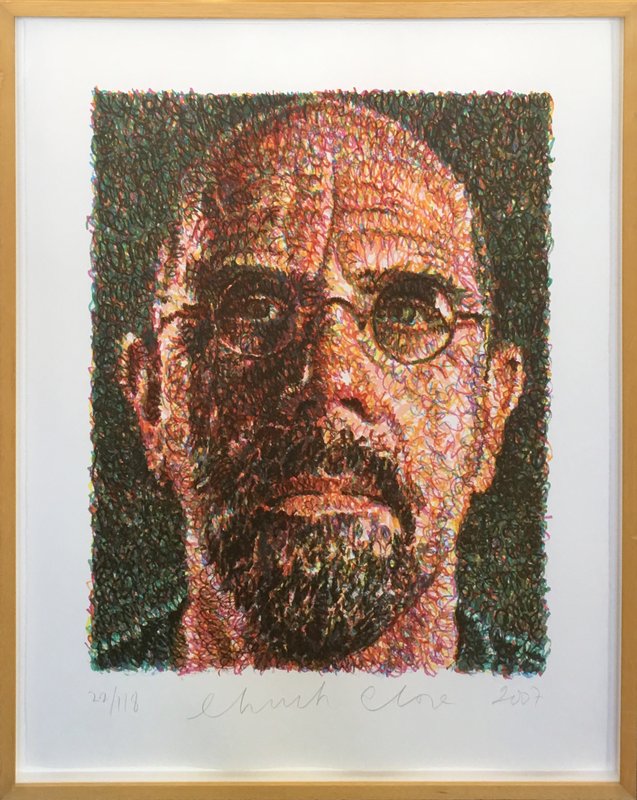

Self Portrait 2007

To read his complete story, visit The Guardian.

When Chuck Close was five years old, his parents asked him what he wanted for Christmas. He told them he wanted an easel. His father, a handyman for the American Air Force, set about making one from scratch.

‘It was,’ says Chuck, 60 years later, his eyes brightening at the memory, ‘a really good easel.’ He used to look at it and wish he had some paints. ‘Times were tough back then,’ he recalls. ‘We lived on a housing project next the air base. My parents didn’t have a lot of money. Then I saw this wooden box of oil paints in the Sears’ catalogue. Man, I wanted that box so bad.’

He wanted it so badly that he can still recall the make: ‘It was a Genuine Weber’s Oil Color Set, with a small white palette included.’

In Martin Friedman’s new book, Close Reading, a kind of friendly critical homage to the artist, Chuck recalls that first painting set with a Proustian relish. ‘I can still, to this day, smell the cheap linseed oil in the tubes of paint. They were fat tubes, not little skinny ones. I knew, even then, that the little skinny tubes were for dilettantes.’

This anecdote is one of several that Chuck Close has at hand to illustrate his childhood sense of destiny, as well as the single-mindedness and unshakeable self-belief that has underpinned his life and work ever since. ‘I know guys in their forties who are still trying to figure out what to do with their lives,’ he says, shaking his head. ‘I knew from the age of five what I wanted to do. The one thing I could do was draw. I couldn’t draw that much better than some of the other kids, but I cared more and I wanted it badly. I have always distinguished myself,’ he says, not boastfully, but matter-of-factly, ‘by being hungrier and being totally committed in an absolutely straight line.’

That straight line has led Chuck Close to where – and what – he is today, an artist who has created a signature style as instantly recognisable as anyone’s since Andy Warhol, one of his heroes. In the process, he has become rich beyond his wildest childhood dreams. The half-finished self-portrait that is mounted diagonally on the back wall of his studio will eventually enter the global art market with a six-figure price tag attached. An early Chuck Close portrait recently sold at Sotheby’s for $4.8m.

‘No one was more surprised than me when my paintings started selling, except maybe my dealer,’ says Chuck, laughing his big hearty laugh, head back, eyes closed. ‘There was a time I could barely get them into a gallery. When I started doing heads in the Sixties, I’d spend four months on a painting and, if I was really lucky, it’d go for thirteen hundred bucks. Even then, that was cheap.’

Heads are what Chuck has done ever since. He calls them ‘Heads’ because when he started painting them portraiture was ‘viewed as a bankrupt form, dead in the water’. Chuck’s heads have defied the dictates of fashion for nigh-on four decades now, attaining a kind of iconic status not least through their similarity. Chuck famously paints from photographs rather than from life. ‘A photograph doesn’t gain weight or lose weight,’ he says, ‘or change from being happy to being sad. It’s frozen. You can use it, then recycle it.’

He is an artist obsessed with the process of making art, as much as with the result. Each photograph is gridded into tiny squares or diamonds, and the canvas, in turn, gridded on a correspondingly larger scale. Bit by bit, Chuck fills in the tiny squares or diamonds with shapes and colours until, out of a matrix of multicoloured squares, ovals and oblongs, a huge face emerges. His critics say that one Chuck Close portrait looks much like another, but you could just as easily say that Chuck’s childhood single-mindedness has evolved into a Zen uniformity of vision that is compelling in its seeming sameness.

‘There’s an obsessiveness there that is extraordinary,’ says Tim Marlow, British art historian and director of exhibitions for London’s White Cube gallery. ‘It has made him a kind of lone figure in contemporary art – no one else is doing what he is doing. He has reinvented portraiture through the medium of paint, but also abstracted it. He’s a painter’s painter, but his reputation is still growing. I’d put him among the top 10 most important American artists since abstract expressionism, no question.’

Interestingly, Chuck paints his own face a lot, too: the big bald head, the Lennon specs, the neatly trimmed goatee. He has made his own face iconic. He also paints portraits of his friends, many of whom seem to be fellow artists: Francesco Clemente, Cindy Sherman, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns. Way back in the Sixties, one of the first heads Chuck painted belonged to the avant-garde musician Philip Glass, who was not so well known back then. To Glass’s surprise – and Close’s – the painting was bought by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the postcard of it became one of their bestselling items.

‘It kept showing up everywhere,’ Glass recalled recently. ‘I told Chuck I never took the painting personally because it was like Monet and the haystacks. I was just a haystack.’

We are sitting at a long table full of books, papers, photographs and lists, in Chuck’s big, white, and otherwise uncluttered studio in downtown Manhattan, near the Bowery. This is Chuck’s turf and, like him, the neighbourhood has undergone a huge change of fortune in the past three decades, from a low rent, no-go zone full of bums and bohos to the salubrious and fashionable quarter it is today.

Chuck whizzes around his studio in a motorised wheelchair, barking orders at his two assistants. In person, he is fearsome and funny by turns, still a big, imposing bear of a man who bristles with impatient energy, even though he has been wheelchair-bound for 17 years. On 7 December 1988, at a ceremony in New York to honour local artists, Chuck was about to present a prize when he felt an intense pain in his back. By the time he had staggered off the podium, the pain had spread into his chest and down his arms. He walked across the road to the Beth Israel Medical Center, where he lay down and suffered a 20-minute seizure. In the previous months, he had been plagued by memory lapses and odd feelings of blankness, but this was much more serious: a collapsed spinal artery.

For a time, Chuck was paralysed from the shoulders down. He can now move his arms and, with some effort, his hands, but his fingers remain immobile. He paints with a brush attached by a harness to his wrist, and uses foot pedals to move his 9ft sq canvases up and down through a long slit in the floor so he is always at eye level with what º ª he is painting. That single-mindedness again.

‘My first thought when I came out of hospital was that I might have to do conceptual work and have someone else execute my ideas, and that made me profoundly sad. Physicality is so important to me in my work. Pushing paint around, that’s what I do. But whatever it takes to get there, I’ll do it. That’s always been my way of thinking.’

Chuck Close is one of life’s combative optimists, and his creative ambition – most evident in the epic scale on which he works – remains undented by his relative immobility. Though he talks 19 to the dozen, he tends to brush aside direct questions about his disability, and has said before that he considers himself ‘lucky’ to be still able to do what he did before his illness. ‘There’s no big difference in the work, really,’ he says, ‘except maybe emotionally. I’d say it’s a little more emotional now, a little more celebratory. The first painting I did after hospital was a little painting of my friend, Alex Katz. It’s profoundly sad-looking, even though the photograph I took of him wasn’t. But, it’s also a brighter palette. It kind of embodies the dichotomy I was feeling at the time: loss, and a great happiness to be back at work against the odds.’

He describes the housing project in Tacoma, Washington State where he grew up as a place where ‘people thought themselves lucky if they had a regular job’. His parents, though, were different. They gave him all the encouragement he needed to pursue painting. ‘My mother was a piano teacher, my father an inventor. He invented the reflective paint they still use on airstrips. They had faith in my ambition, and I think that made all the difference. I always used to say it was, “Go to Yale or go to jail,” and there was some truth in that. I had no fallback. If art didn’t work, I was fucked.’

Despite his dyslexia, which went undiagnosed for a long time, Chuck won a scholarship to the Yale summer school and then Yale proper, where his classmates in the early Sixties included the artists Richard Serra and Michael Craig-Martin. It was the era when abstract expressionism, the great big, messy, macho American style of painting, was on the wane, but its influence lingered. ‘Abstract expressionism depended on the rendering of angst,’ says Chuck, laughing, ‘and I didn’t have any angst. I hadn’t suffered. In a way, we were just imitating the surface of all that stuff, Pollock and so on, and there’s nothing worse than fake angst.’

While at Yale, Chuck remembers going out drinking with two of his tutors, Jack Tworkov and Philip Guston, abstract expressionists both, the latter having not yet pulled off his spectacular reinvention as a raw figurative artist.

‘We’d go to the Old Heidelberg in New Haven and drink strong German beer into the night. One time we got really drunk and they both started crying. There’s Jack on one side, wailing, “I ain’t sold a goddamn painting in a year and a half” and Philip on the other, going, “I haven’t sold one in two goddamn years.” And me in the middle, just devastated. But they reinvented themselves.’ He grins, his eyes light up. ‘They came back stronger. That was the most important lesson of all for me.’

Later, Chuck would do the same. He stopped making abstract work and in 1966 started painting big portraits from photographs.

‘It was a time of theoretical ferment. Everyone of my generation was trying to start over, trying to figure out what they were doing. America was on fire – Vietnam, the assassinations. We were a product of all that but we did not attempt to make directly political work. It seeped in in other ways, in this questioning of everything you took for granted. The Sixties to me was one big question.’

His answer was, as he puts it, ‘to make forward-looking, modernist representational paintings, including portraits, that were just as rigorous and tough and unlikeable as abstraction’.

In 1967, he moved to New York. His first major work was Big Self-Portrait, a monochrome ultra-realist painting that has since become one of contemporary art’s iconic images. In it, he looks both cool and nerdy, perhaps stoned, his tousled hair framing eyes that stare impassively at the viewer from behind geek spectacles. A half-smoked cigarette sticks out the side of his mouth beneath big nostrils and a sprouting moustache. It’s an image that is utterly of its time, yet possesses a strange contemporaneity. ‘I was in there early with the grunge look,’ he says, grinning.

Was it a natural pose or a created one? ‘Oh, created. Totally. I didn’t want it to look flattering or distinguished like a traditional portrait. It was an effort to put mileage between me and what portraiture had become. Hence the shirt coming off, the cigarette, the stubble. Clement Greenberg had said that there was one thing an artist could not do any more and that was paint a portrait. I thought, that’s good, that’ll keep the competition down. I just dived in there, I guess, tried to make it new again.’

It took some time, though, before Chuck Close’s ‘heads’ were looked upon as something new; longer still for Chuck, himself, to admit that his ‘heads’ were actually portraits. ‘I was asked to do the Artist’s Choice show for MoMA when I came out of hospital, where you select works you love from their collection. I found hundreds of portraits, and they were so not what you expected of modernism. That’s when I realised I’d been fooling myself, that I was a portrait painter all along, I was the caboose of the train of portraiture.’

Over the years, Chuck’s heads have become bigger and brighter, somehow more real and yet more unreal. His latest gargantuan self-portrait looks like a pixellated colour photograph, but the closer you move towards it, the more abstract it becomes, until you might as well be staring at a formalist landscape of colours and patterns. We look at it together. ‘The strange thing is,’ he says, ‘I don’t know what a face looks like unless it’s flattened out. That’s one of the things about my learning disability. That’s why the photograph works for me. In real life, if I saw you again tomorrow, I would have no idea I had seen you before.’

I think about this for a while, and it makes what I am looking at even more extraordinary. Likewise, the man who created it. ‘Painting for me is like putting rocks in your shoes before you go out on a journey,’ he says. ‘It’s about making things a little more difficult for yourself so that you know where you are going, but you never really know how you’re going to get there. They used to say that Pollock didn’t know what his next painting was going to look like, but he did know what he was going to do in the studio that day. Me, I know what my next painting is going to look like, but I don’t know what I’m going to do in the studio to get there. I’m just trying to inch nearer all the time.’

· Chuck Close is featured in the exhibition Self Portrait: Renaissance to Contemporary at the National Portrait Gallery from 20 October, and is in conversation with Tim Marlow on 21 October. Close Reading: Chuck Close and the Artist Portrait by Martin Friedman is published by Abrams at £24.95