Maurice Denton Welch was born March 29, 1915, in Shanghai, to Arthur Joseph Welch, whose parents were English, and Rosalind Basset, whose family was originally from New Bedford, Massachusetts. Denton Welch was the youngest of four boys and spent his early childhood in Shanghai, with many visits to England.

In 1924 Welch was enrolled in a school in Kensington, and then from 1926 to 1929 he attended St. Michael’s, a preparatory school in Uckfield, Sussex. While he was in school, his mother, with whom he was especially close, died in Shanghai during March 1927; this event had a profound effect on her son. In 1929 Welch started attending school at Repton in Derbyshire. Welch started at the Goldsmith School of Art in New Cross in 1933, where he studied for three years; among his teachers was the printmaker and graphic designer Edward Bawden. At first he lived in a house where his brother Bill was also rooming, and then he moved into a house near Greenwich Park where the landlady was Evelyn Sinclair, who became a close lifelong friend.

On June 7, 1935, Welch was traveling by bicycle to go visit his aunt, when he was hit by a car. His spine was fractured, and for a few months he was paralyzed from the chest down. He was able to learn to walk again, but with difficulty. For the rest of his life he had kidney and bladder infections, which would cause frequent severe headaches. After the accident, Welch first spent time at National Hospital, and then in the Southcourt Nursing Home in Broadstairs, Kent. When he left the nursing home July 1936, Welch rented an apartment with Evelyn Sinclair in Tonbridge in order that he could be close to his doctor, John Easton. Sinclair remained with Welch as his housekeeper at his different residences until May 1946, two months after Welch and his partner Eric Oliver moved to Middle Orchard, the country house of Noël and Bernard Adeney at Crouch, near Borough Green, Kent. Sinclair returned to Middle Orchard in July 1948 to assist Welch until his death.

Welch continued to paint and draw after his accident. In 1941 the Leicester Galleries in London first exhibited some of his paintings, and continued over the next few years to include his paintings in their exhibits. The Leger Gallery and Redfern Gallery, both in London, also exhibited his works.

Welch began writing in 1940, and some of his poems appeared in minor publications in 1941. In 1942, after the death of the painter Walter Sickert, Welch’s article “Sickert at St. Peter’s” (an amusing account of his having tea with Sickert shortly before Welch left the nursing home in Broadstairs) was published by Cyril Connolly in the August Horizon. Welch received a letter of praise from Edith Sitwell. Soon after, Herbert Read, editor at Routledge, accepted Welch’s manuscript for Maiden Voyage, and Dame Edith offered to write the foreword; she also wrote a review for the book. With her support, Maiden Voyage sold out before its May 1943 publication. The book received enthusiastic reviews, and Welch began writing In Youth Is Pleasure, which was published in February 1945. He also wrote several short stories, and in the fall of 1945, as his health was worsening, Welch resumed his work on A Voice Through a Cloud, a novel that he had begun earlier, and that was to remain unfinished at his death. Although Welch was to consider himself primarily a writer after the success of Maiden Voyage, he kept painting and drawing. Nine of his late paintings, created during a time when his health was failing, were reproduced in A Last Sheaf (published in 1951). He died December 30, 1948, at Middle Orchard Cottage in Crouch, Kent.

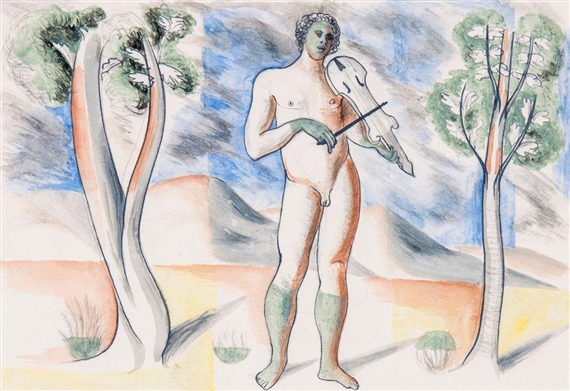

Self Portrait 1942

For nearly half a century Eric Oliver (born Bromley, Kent 6 October 1914; died Portslade, East Sussex 1 April 1995) basked in the reflected glory of having lived with the writer Denton Welch for the last four years of his life. (P: Eric Oliver in 1947)

For nearly half a century Eric Oliver (born Bromley, Kent 6 October 1914; died Portslade, East Sussex 1 April 1995) basked in the reflected glory of having lived with the writer Denton Welch for the last four years of his life. (P: Eric Oliver in 1947)

Oliver was introduced to Welch in November 1943 at a time when Oliver, a conscientious objector, was working on the land and Welch was living as a semi-invalid, following a disastrous road accident when he was 20, near Hadlow, in Kent. “After you left the other night,” Welch wrote to the painter Nol Adeney, “who should appear but Francis [Streeten, one of Welch’s more eccentric acquaintances] and a new hearty land-boy friend! The land-boy kept suggesting that I should get up and go out and have a drink with him! As I was almost a corpse by then, I could not oblige.” He elaborated in his Journals: “I tried to be very bright; but it was an awful strain. They had been drinking in a pub and had come on to me later. They were still mildly redolent of the pub and beer.”

Despite Oliver’s boozy and often hurtful conduct, Denton Welch fell in love with him. The intensity of Welch’s emotions was not returned, for on his own admission Oliver was incapable of love (“You must never take me seriously,” he wrote in the only letter of his to Welch which survives), but, once they had sorted out the imbalance in their relationship, Oliver moved in with him, and as Welch’s physical condition deteriorated Oliver nursed him with practical expertise.

On the face of it, Eric Oliver seemed an incongruous choice of companion for a writer and painter as fastidious as Denton Welch. “It is just because you are different that I like you,” Welch wrote to him in February 1944. “You wouldn’t touch my imagination in the very least if you approximated more to my type.” Oliver was virtually illiterate, and had little judgement about people, art or business. As Welch’s residuary beneficiary on his death at the tragically early age of 33 (inheriting about £5,000), he appointed himself his literary executor, but parted with the copyrights of Welch’s works to a bookseller who promptly resold them to the University of Texas. Oliver always maintained that he did not understand what he was signing.He wrote that (emetically sentimental, wrenchingly wistful) desire from the crooked perspective of injury and damaged youth. As a statement, it interests me in that it comes from a literalized version of that perennial fantasy of the old: the wasted and damaged youth. For Welch, this fantasy was a reality, and the desire to have it undone, to pull back the cheap threads of time was more violent and truly spoken than the common bad-faith regret of the old. Although, a voice (through a cloud?) whispers into my ear with the warmth of seduction, “We all waste our youth. At least he had a real excuse; you certainly do not.https://themenaceofobjects.wordpress.com/2014/04/

Portrait of Welch in 1935 soon after accident by Gerald McKenzie