Hogarth to Vagabondiana by Simon Jarrett

We are going to look today at two visualisations of disability in the eighteenth century, firstly from the artist William Hogarth in the middle of the century and then in a book from 1817 called Vagabondiana, by John Thomas Smith, which took a rather nostalgic look back at the London street beggars from the end of the eighteenth century, using sketches and potted life histories.

There was a very high prevalence of physical disability in this period: as well as being born disabled, often through a lack of obstetric care during birth, you could also become disabled through a large number of disabling diseases, accidents caused by carriages and horses in the teeming streets, dangerous workplaces, potholed streets and collapsing buildings. Of course there were also many disabled soldiers and sailors from the numerous wars of the period. The playwright John Gay, author of the Beggar’s opera, warned people to be careful when walking round Lincolns Inn Field at night lest they trip over the crutches of the many hundreds of beggars that gathered there.

I hope to show not only the often ingenious types of mobility aid that were used as technological fixes for the many who needed them, most of whom were very poor and therefore needed to fashion aids from the most basic of resources, but also the moral and symbolic meanings that these objects carried for the eighteenth century British public, which framed their understanding of and response to disability. You will notice that it is only at the end of the century that any form of wheeled mobility methods of transport start to emerge – the most simple explanation for this is that until then it was only the centres and major streets of large cities such as London that were paved – the other streets and alleys were highly congested and obstacle-strewn dirt roads, that would turn to mud at the first sign of any rain, making small-sized wheeled transport virtually impossible. The later extension of paving across a wider area brought about an increase in use of wheels, as we shall see.

We begin with William Hogarth, who may be familiar to many of you, who was a great artistic chronicler of the 18th century’s everyday events and ordinary life before the age of photography. He is perhaps most famous for his ‘morality’ tales, such as the Harlots Progress, the Rakes progress, Marriage la Mode and Idleness and Industry, in each of which series of paintings young people fall into a life of vice and immorality, and endure terrible consequences for doing so. Despite being a conservative figure both in political and moral terms, Hogarth showed a great empathy with the people of London and everyday London life, and often displayed a sneaking regard for the vice, drunkenness and sexual immorality he was ostensibly denouncing.

Here is a print you may know: Gin Lane, which depicts the appalling consequences of the cheap gin-drinking craze that afflicted the poor parts of London for about 40 years, causing tens of thousands of deaths and desperate misery and poverty. You may be less familiar with its companion piece, Beer Street, which depicts the virtuous consequences of drinking good old British beer – virtually a religious and political duty for the English at this time.

In Gin Lane we can see Hogarth’s portrayal of abject misery and moral collapse. The baby falls to its death from the arms of its paralytically drunk, semi-clothed mother. With its famous motif ‘Drunk for a penny, dead drink for tuppence, we see buildings collapse – collapse and falling over are an important indicator of moral collapse which you will see in many of Hogarth’s paintings – and the only buildings which are stable are the pawnbrokers, the undertakers and of course the gin distillery. Bearing in mind this idea of collapse and instability being associated with moral degradation, look at this group here in the background – a mass brawl is breaking out and it consists of disabled people attacking each other with their sticks and crutches – you can see one to the edge of the brawl about to go over backwards desperately clinging onto his crutch. Here Hogarth is associating the idea of disability – the inability to stand on your own two feet if you like – with moral disorder and decay. If we then look at Beer Street you will see the complete opposite of Gin Lane. Comfortably overweight and prosperous men suck on their pipes and quaff their ale, fondle their alluring, key-dangling women. The buildings stand proud, particularly the brewery with its beautifully balanced barrel hanging from it – the only building that is crumbling, in contrast to Gin Lane, is the unused pawnbrokers. If you drink good British beer, life will be good and trade and commerce will prosper, in contrast to that dreadful foreign import of Gin, or Geneva as it was known. Note, however, that in the depiction of Beer Street there is not one stick or crutch to be seen. In a prosperous, moderate, balanced, well ordered society, the body is not afflicted with the diseases of poverty and immorality – everything is balanced, people stand on their own two feet. In this way, the stick, crutch or other sorts of mobility aid could symbolise some loss of human status, a loss of that ability to order yourself, a prop to just about cling on to your status.

A stick or crutch signified a move away from full human status towards a more intermediate status, and the same process could happen the other way. An animal with a stick could indicate a lower species moving towards human status. This drawing is from Edward Tyson’s influential book from 1699 in which he described a young chimpanzee that had been brought from Angola in Southern Africa. Hogarth would almost certainly have read this book. There was much speculation as to whether there might be an intermediate species between apes and humans, or even some types of ape that might be a new species of human. The chimpanzee, or Pygmie as it was known at the time, was a particular object of speculation. Tyson concluded that it was not a form of human, but that it did have characteristics that closely resembled humans, suggesting that it might be an intermediate species, one of which was the ability to walk on two legs. In fact chimpanzees can’t do this, like other apes they apply their knuckles to aid their walking and therefore use all four limbs, but Tyson concluded that his Chimp would be able to walk if only it wasn’t feeble and ill from the long journey it made (it died after several weeks). However, being a scientist dedicated to accuracy, he could only bring himself to portray the chimp walking with the aid of a stick – this both acknowledged that Tyson had never actually seen it walk on two legs, but also symbolised the intermediary status between human and animal that he believed his Pygmie had.

Hogarth picked up on this and frequently portrayed animals tottering towards human status by getting onto their hind legs, just as he depicted humans tottering away from their status by having to use artificial aids to do what was seen as the fundamental human task of walking. Here, 1745, in his portrayal of his friend Lord George Graham, an admiral of the British navy, he depicts a series of slippery identities – Lord George Graham out of uniform and without his wig, the girlish cabin boy, the relatively high-status black drummer and last of course the dog, standing on his hind legs, and wearing a wig.

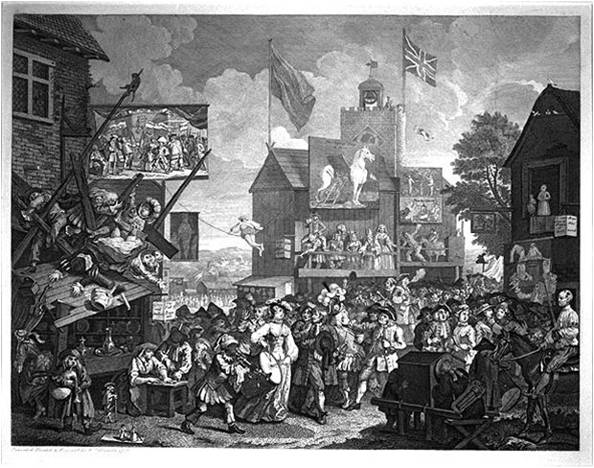

H

H ere in Southwark Fair 1732, a typical Hogarth portrayal of a riotous, disorderly London scene, you may just be able to spot this small dog striding in a very human like way across the picture with the aid of a stick. In such a disorderly world, Hogarth is telling us, such a thing would be no surprise.

ere in Southwark Fair 1732, a typical Hogarth portrayal of a riotous, disorderly London scene, you may just be able to spot this small dog striding in a very human like way across the picture with the aid of a stick. In such a disorderly world, Hogarth is telling us, such a thing would be no surprise.

The association of the stick with disorder and lesser human status can be seen in Hogarth’s Noon,1738, which depicts the coming together of two widely different sections of London’s community. On one side the disorderly but jolly native Londoners (one of whom is black interestingly) who are coming out of the ale house, the man fondling the woman’s breasts, she becoming so distracted that she spills her hot pie gravy onto the bawling baker’s boy, who in turn drops his wares onto the floor where they are hoovered up by a hungry young girl. Opposite them, coming out of church of course, are a group of austere, earnest French Huguenots, protestant refugees from religious persecution in France who have prospered in London and who Hogarth clearly sees as a rather po-faced, pretentious, miserable lot. Note that here he uses the stick in two ways – first in the rather affected gentleman it is purely an ostentatious, luxury fashion item, with no practical purpose. But notice that there is also a rather obnoxious child, dressed in the wig, frock coat and stockings of an adult. A child dressed as a man, just like an animal imitating a man, needs a stick to support it, once again the stick or mobility aid drawing our attention to intermediate status.

Which brings us to Hogarth’s Election series, a group of paintings satirising the abject corruption and mob-violence of the Whig/Tory political conflict that raged throughout the century. Here, in ‘The Polling’,1758, a disabled war veteran is trying to cast his vote. He has lost both hands, and on his left arm he has a hook. He has also lost his right leg, and has a wooden leg in its place. What is happening is that pompous lawyers are debating whether it is acceptable for him to swear the necessary pre-voting oath by laying a hook on the bible rather than a hand. While his vote is denied, behind him a group of enfeebled, demented, semi-conscious and idiotic people are lined up to vote, their hands guided onto the ballot papers. Clearly Hogarth is satirising electoral corruption, but he is also introducing the concept of the deserving disabled – the war hero, who has sacrificed his body in the service of his country, is denied and excluded, while the feeble minded, the non-deserving disabled, are indulged. Note his heroic posture, front foot thrust forward and his wooden leg firmly supporting him, his handless arms heroically thrust back. He uses no stick or crutch to balance himself, he can stand on his own two feet, even if one of them is wooden. We see something similar in this further painting from the election series, ‘Chairing the members’ where the candidates are chaired through the streets of Oxford by their respective supporting mobs, one of them looking as if he is possibly about to join the ranks of the disabled himself (note the recurring tumbling/collapse motif again) But note this man here, another disabled war veteran, about to lay into his political opponent with a cudgel. Again we see the heroic posture and stance, his weight firmly on his wooden leg, no supporting stick or crutch, and fully engaged in the action and everyday life. Note also that his opponent clearly does not think it necessary to go easy on him because he has a disability.

This placement of people with disabilities at the heart of everyday life can also be seen here in this depiction of a cockfight,1759, and the group of rowdy gamblers and cock fight enthusiasts. At the heart of it all is a blind man – actually representing the real life figure of Lord Albemarle.

He has an almost saintly, religious air, but note his vulnerability as the man next to him craftily pinches money from his winnings laid out in his leather pouch before him. To the side of the picture we see a man who is both physically disabled and deaf, sporting his crutch while his servant shouts a commentary on the cock fight into his ear through an ear trumpet. Multiple disabilities were not an insurmountable obstacle to being out and about and at the heart of the community – there was always some ingenious technological fix.

Here is the first plate of Marriage a la Mode Plate 1, Hogarth’s morality tale about the marriage between the feckless son of an aristocratic father and the equally feckless daughter of a nouveau riche merchant. This is a marriage of convenience, the idle ancient aristocratic family have squandered their wealth and need a fresh injection of cash, the merchant needs the elevated social status to go with his newly acquired wealth. The family tree of the Lord is displayed at his side, to demonstrate the noble lineage of his family, but next to it is propped his crutch – a very finely crafted and velvet-topped crutch – to portray the physical and moral degeneration of his family. His right leg, bandaged, rests of a footstool, indicating that disabling disease of over-indulgence, gout.

Plate 6 Marriage A La Mode 1755. If we move now to the final tragic scene of the series, the countess sprawls dying in her chair, having committed suicide, unable to bear the news of the death of her lover, the appropriately named lawyer Silvertongue, who has been hung for murdering her husband the count, after he discovered their affair. Her child, probably a boy, is held to her face for a final kiss, as her father prudently removes the gold marriage ring from her finger to use another day.

An everyday story of 18th century folk, but look closely at the child – here on his leg you will see callipers, indicating that he is disabled, and here on his left cheek is a black spot, indicating syphilis. The child has suffered for the moral degradation of his parents, and they have passed disease and disability to him. Incidentally, also note here the idiot servant, being berated by the apothecary for having haplessly bought the poison which the countless has used to kill herself. One clue, of many, to his idiocy, is his wrongly buttoned servant’s livery. The painting is full of disability motifs.

Here, above, is a plate from the ‘industry and idleness’ series, which charts the lives of an industrious and an idle apprentice. The industrious apprentice works hard, marries his master’s daughter and becomes London’s mayor. The idle apprentice is seduced by gambling, promiscuity and crime and ends life on the gallows. A straightforward morality tale. Here we see the industrious apprentice celebrating his marriage to his master’s daughter, and a collection of beggars, including a beggar band, gather at their door, hoping for celebratory gifts. Here on the left is ‘Philip in a tub’, a known character from the London streets. Philip had no legs, and mobilised himself by sitting in a wooden tub or bowl and then using two short crutches to slide himself

along. This form of mobilisation was common for people without legs, and they were nicknamed ‘Billies in Bowls’ in the rich slang of the time. He is selling ballads, a common form of employment for disabled beggars, similar to selling the Big Issue today. Note how Hogarth has captured his incredibly powerful upper arms, developed through pushing himself using the crutches, [slide 20] reminiscent of David Weir, Britain’s fine Paralympian athlete.

mobilisation was common for people without legs, and they were nicknamed ‘Billies in Bowls’ in the rich slang of the time. He is selling ballads, a common form of employment for disabled beggars, similar to selling the Big Issue today. Note how Hogarth has captured his incredibly powerful upper arms, developed through pushing himself using the crutches, [slide 20] reminiscent of David Weir, Britain’s fine Paralympian athlete.

And finally from Hogarth here is the fitting end of the idle apprentice, who is brought to Tyburn to be hung for his crimes before the huge crowds that gathered there on execution days. The character of interest to us is another disabled war veteran, here at the back of the crowd.

His head bandaged, he rests his mutilated leg on an upside-down V shaped wooden support with a curve built in to take his knee. From the top of the upside-down V extends a crutch which tucks under his armpit. I am not sure how he would move with this, but my guess is that he would hop with his left foot and then swing forward the contraption supporting his right side. The ingenuity of this adaptive technology to accommodate his particular disability is striking – and it is course fashioned at virtually no cost from a piece of wood.

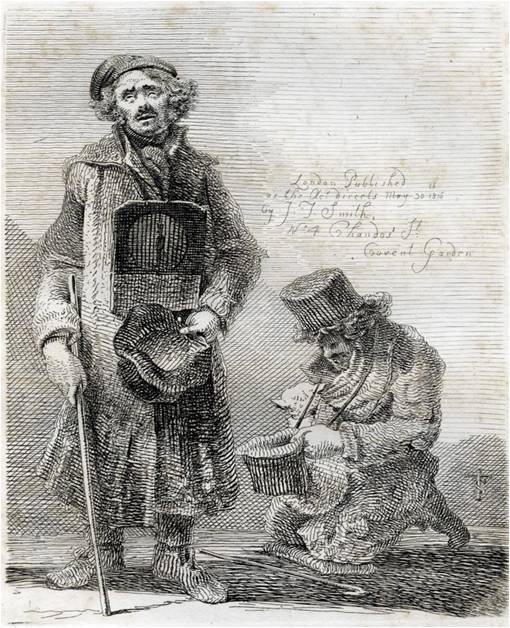

Moving forward half a century from Hogarth to John Thomas Smith, we encounter an array of street beggars, many of them disabled, and beautifully sketched in his publication Vagabondiana of 1817.

Smith, known as ‘Antiquity Smith’ was an antiquarian dedicated to preserving the fading past, and he published this in the belief that beggars would disappear from London streets in the wake of new legislation which would move them from the street to institutions such as workhouses, as part of the moral and physical clean-up of London which occurred with evangelical zeal in the 1790s and early 1800s. He could afford therefore to be quite sentimental and nostalgic about these characters, as any threat they might once have posed had now disappeared. [slide 24] This first image symbolises this change, as we quite literally ‘see the backs of’ three disabled beggars as they leave the town for the workhouse on its outskirts.

Once again the dog appears, performing a threefold function, much as they do for street beggars today: companion or friend to the often isolated beggar, magnet to the public to attract extra donations and, if the beggar is disabled, guide or assistant. This first dancing dog – able to stand on his own two feet – was known as the ‘the real learned French dog Bob’ who would dance to solicit donations as his blind master played the barrel organ. The second dog, holding the begging bowl, would whine pitifully when its master called out ‘pray pity the blind’. Both of these dogs would also have acted as guides for their masters.

Here is an even more functional disability helper dog. The beggar here is John McNully, an Irishman whose legs were crushed by a log and who ended up on the London streets. He got himself two dogs, known imaginatively as Rover and Boxer, and trained them to pull him on a small sledge. Again this was a common mobility adaptation, and brought into being the slang term ‘sledge beggar’. The two dogs were apparently such an attraction that they doubled McNully’s takings. It was said that when he would get drunk on the generous proceeds of a day’s begging, Rover and Boxer would unerringly drag the comatose McNully back to his lodgings, even finding a diversionary route when they were blocked by street repairs.

This had now become a popular mode of disabled transport, as usable paved streets proliferated in cities, as this sketch by Goya – ‘Yo lo he visto en Paris’ (I saw it in Paris) from the 1820s indicates.

And here is a Jewish beggar, in a wheeled cart, who was pulled (by human helpers) to various locations around Petticoat Lane to solicit donations. His venerable appearance, Smith remarked, meant that Christians as well as Jews were happy to donate to him. Inevitably a slang term emerged to describe this form of disability transport – it was a go-kart, an expression we still use today. And so the representations go on – a beggar who solicited donations at Poets Corner at Westminster Abbey, his cleverly targeted market the intellectual sensitive types that would pass by in that area – note that unlike the war veterans he does use crutches to support himself as well as his wooden leg. This may well have been through pure physical necessity, but also he is presenting himself in what has been called the ‘rhetoric of pity’ to draw attention to his afflictions. Others pooled together to present a combination of physical and social misfortunes. The blind beggar stands with the physically disabled beggar, his cane indicating his blindness. (White canes were not introduced until after World War I by the way). He was a British soldier who had been blinded in Gibraltar but chose to present himself as foreign, calling out in an indeterminate accent ‘de money, de money, go very low too.’ His calculation was that the double misfortune of being blind and not being British would attract additional generosity.

The opposite approach was taken by this black beggar James Johnstone, a former sailor who became disabled in the course of duty and ended up on the streets. Note that as well as the crutch and stick he displays himself with a model ship on his head.

This was a model of the suitably patriotic HMS Nelson that he had made himself, and he would pass by people’s windows ducking and raising his head to make it look as if it was riding the waves. He would also sing patriotic sailor songs such as ‘the wooden walls of England.’ His presentation aimed to show that as a black disabled beggar, he was a patriotic black British man, who had served his country, and was not to be feared or despised. This was a self-presentation as a deserving disabled person.

Blind beggars as well as dogs also used child guides, who had a reputation derived from a long history of ‘trickster’ stories of being mischievous and deceitful and just as capable of tricking their blind masters as helping them – note the mischievous expression of the child in this drawing. Or they would negotiate the teeming streets of London with ever-longer canes – the blind beggar in this print is described as ‘beating the kerbstones with his cane’ as he walked.

And finally, note just once more the ingenuity of design fashioned from the most basic of resources to provide adaptive solutions to complex disabilities. Here a beggar with two amputations to the lower legs at different heights rests his knees on two differently-sized wooden blocks to give him balance and mobilises himself with two sticks.

So to finish, in an age where notions of disability were at times closely linked to Enlightenment fears about order and disorder and political instability, and where the nature and origin of your disability could determine whether you were seen as a deserving or undeserving disabled person, we should not forget the sheer ingenuity with which disabled people negotiated a complex world and ensured that they remained very much a part of it.

Simon Jarrett simonj@jarr.demon.co.uk Birkbeck University of London Research Supported by Welcome Trust